Impacts of Covid-19

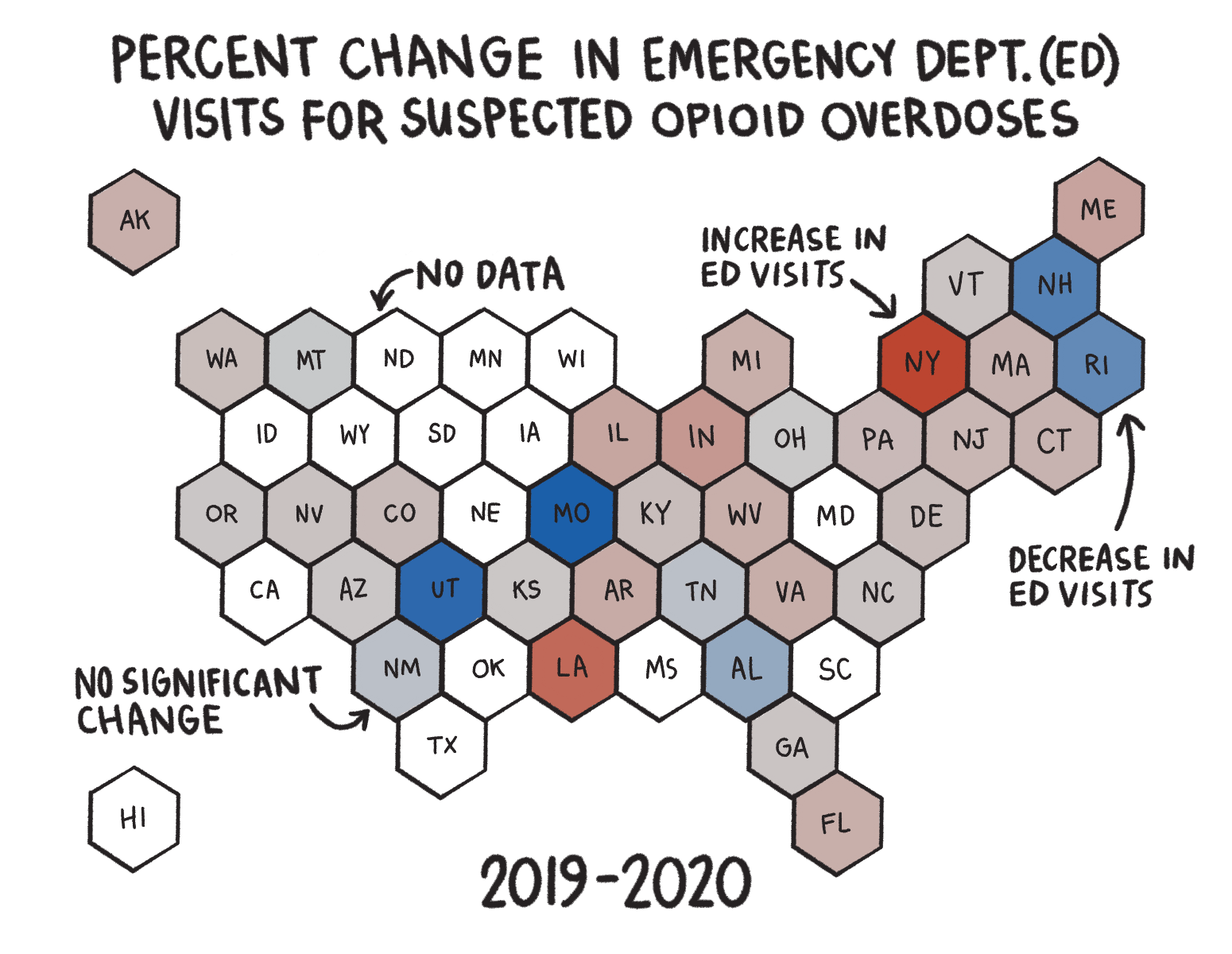

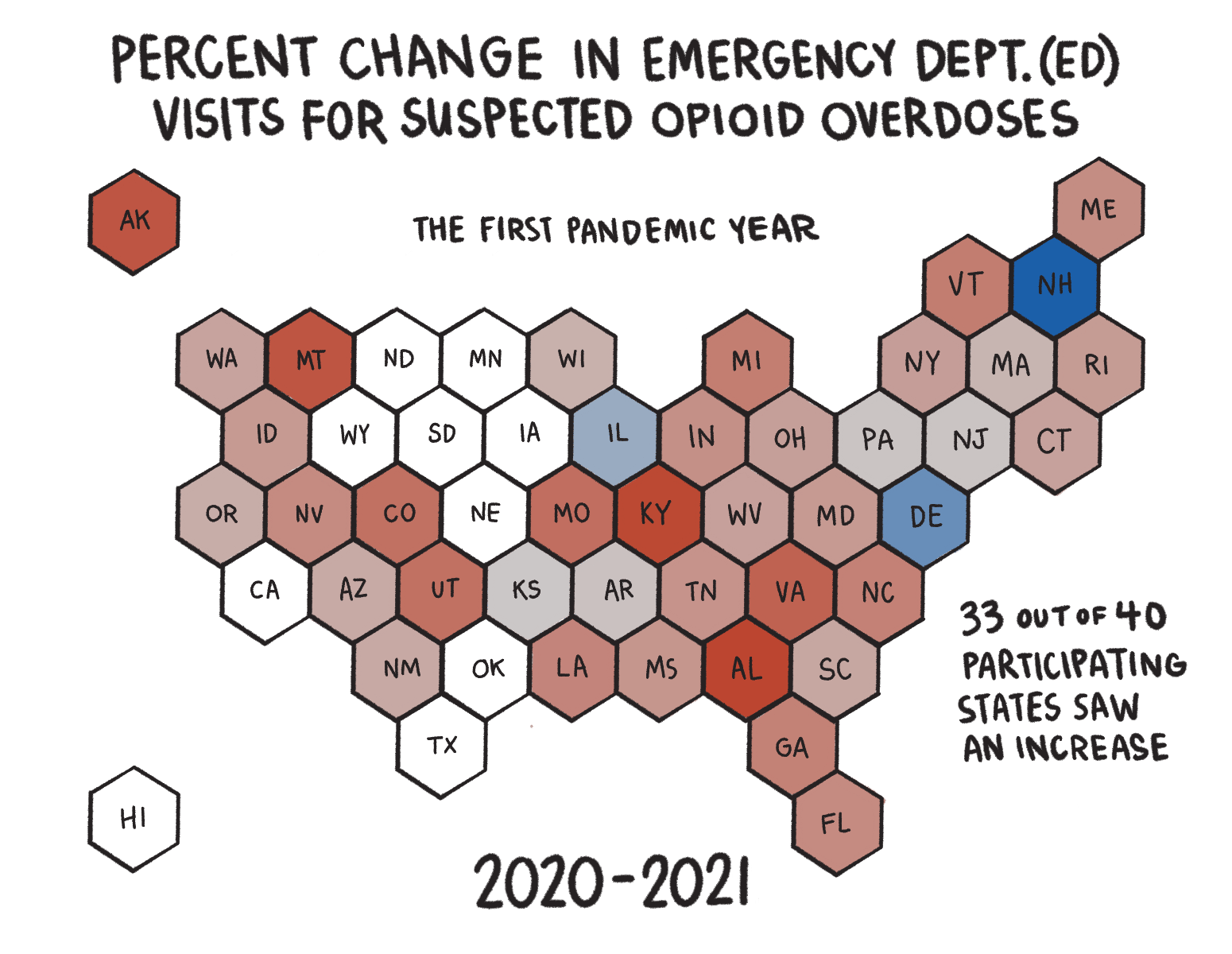

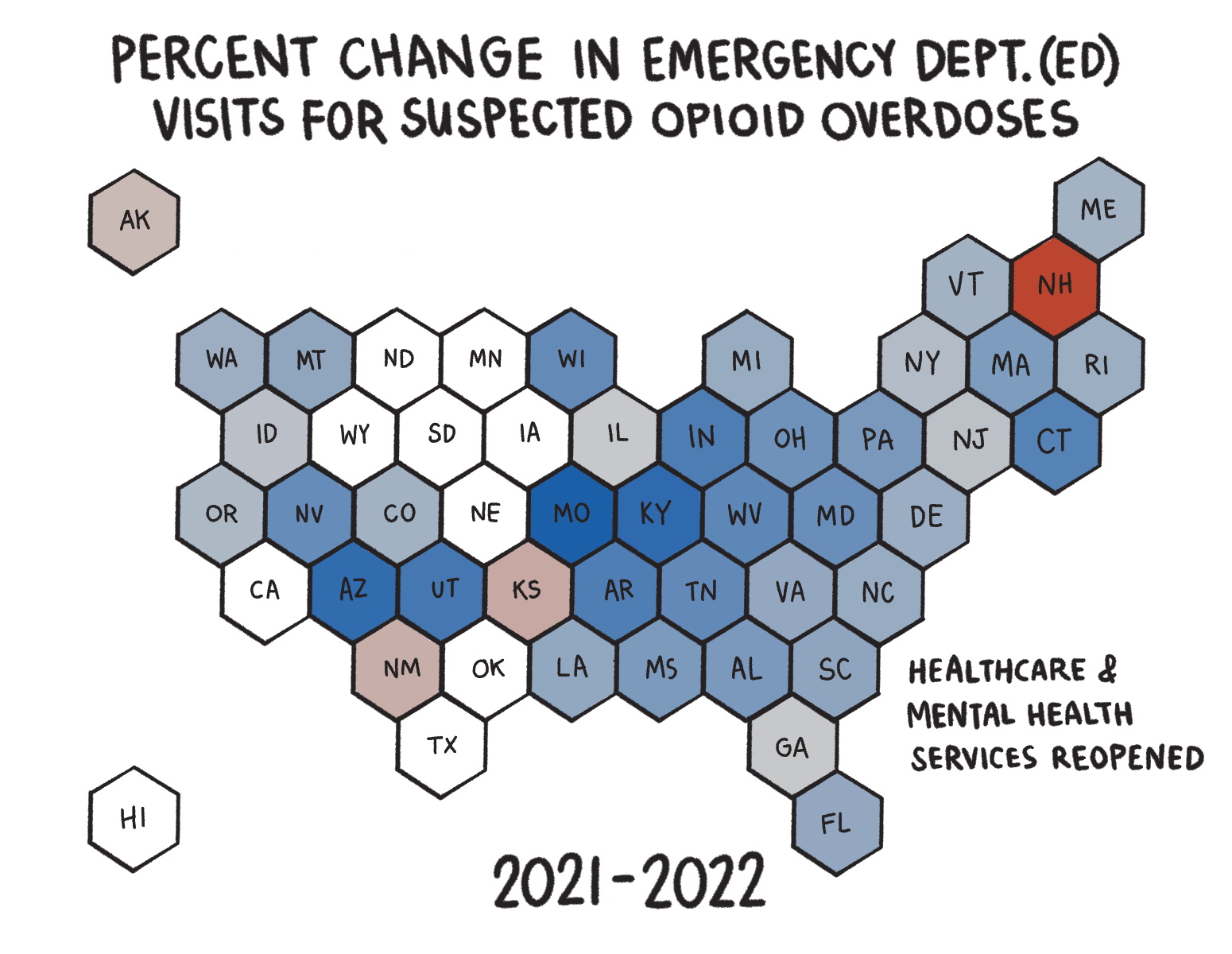

Covid exacerbated the opioid epidemic. Although overdose rates were going up before the pandemic, isolation, disruption of addiction services, and other factors related to COVID increased overdose rates further.

Illicit Fentanyl

Beginning in the 2010s, drug traffickers capitalized on the addictive nature of opioids and flooded the United States with alternatives to prescription pills, like heroin and illegally-made fentanyl.

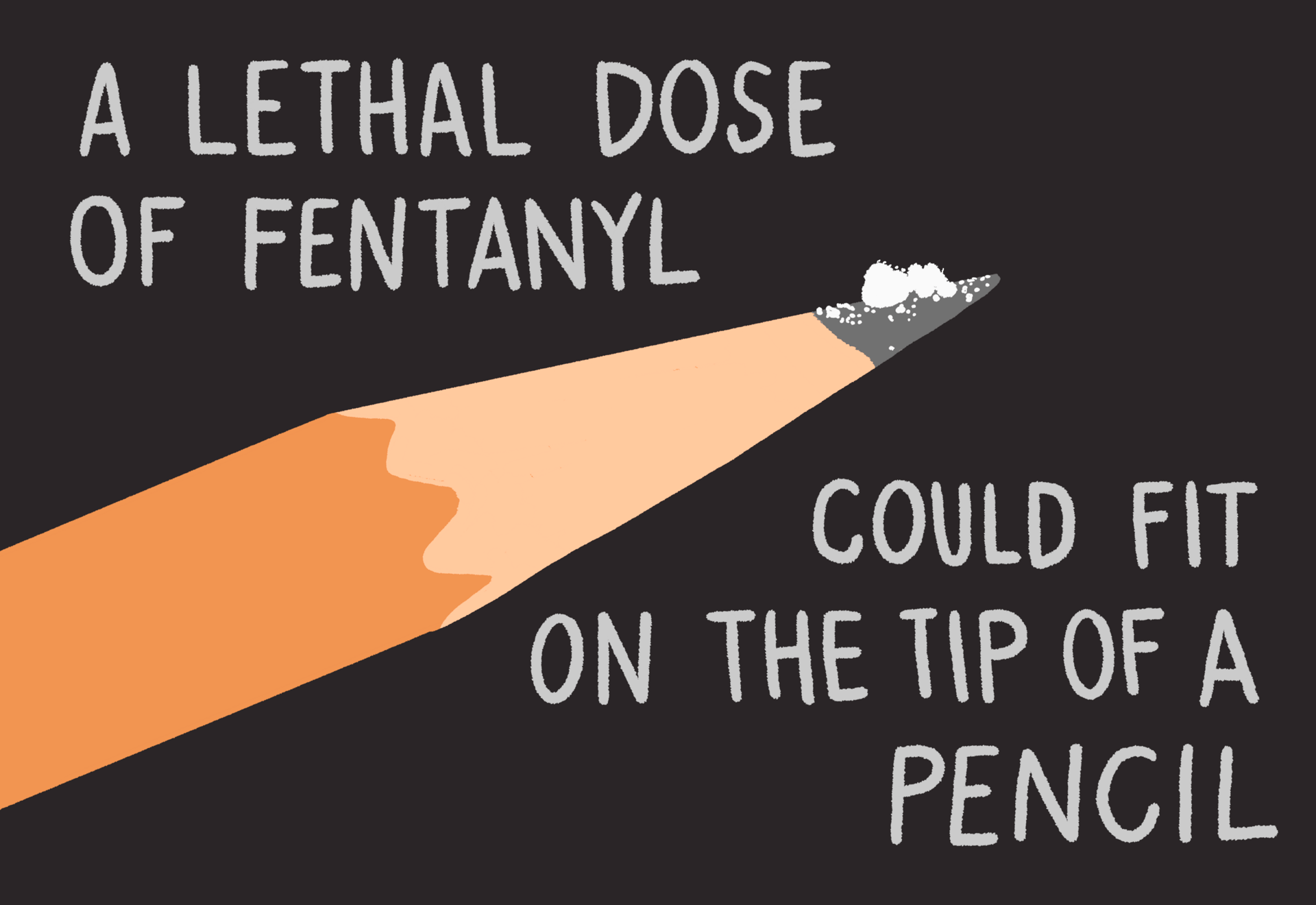

There was no demand for fentanyl at first since fentanyl can be deadly and provides only a short-acting high. However, it takes very little drug to produce a high with fentanyl, and it is much easier to produce than opiates like heroin, making it a cheaper option for dealers to make and sell.

Big Pharma

Starting in the 1990s, the U.S. health care system, Purdue Pharma and other pharmaceutical companies flooded the United States with opioid painkillers. Opiates, the type of opioid found in nature, have been recognized for their medicinal and psychoactive properties for over 5,000 years. Humans have known these drugs can lead to tolerance, addiction, and death.

Pharmaceutical companies, in collaboration with drug distributors, pharmacies, and the consulting firm McKinsey & Company decided to tell a different story about opioids. They marketed and promoted opioid painkillers, like OxyContin, as non-addictive due to a new feature, a time-release coating.

These companies marketed opioids to patients and doctors across the country, misrepresenting the duration of pain relief, falsely claiming superiority to other treatments, and falsely misrepresenting and downplaying the risk of addiction.

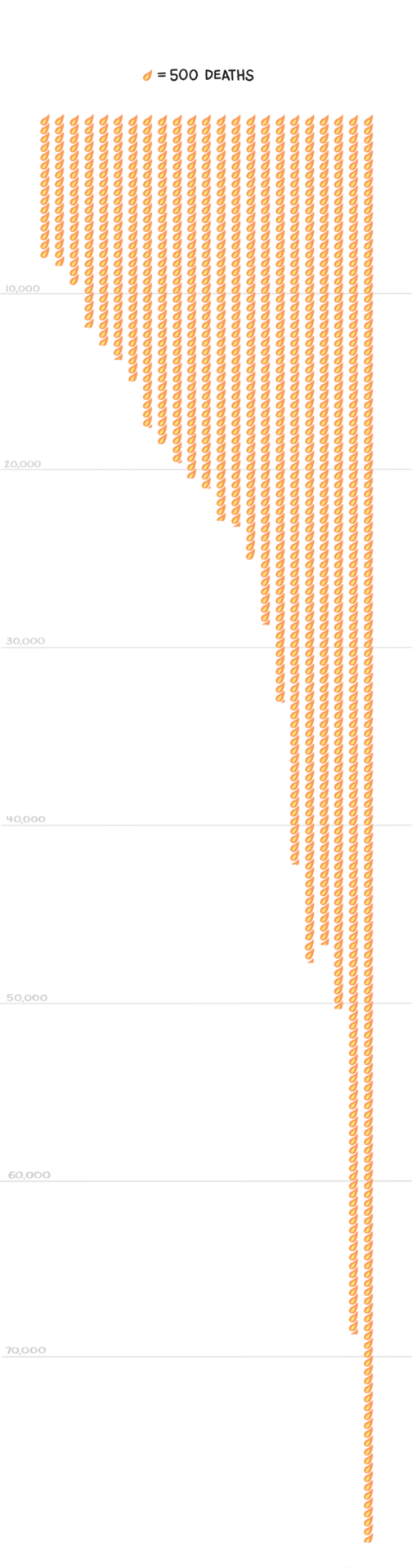

In 2021, 80,411 people died from an opioid overdose.

That’s nearly a 900% increase from 1999.

In 1999, 8050 people died from an opioid overdose.

Over the past 22 years, overdose deaths from opioids have increased exponentially.

What are opioids?

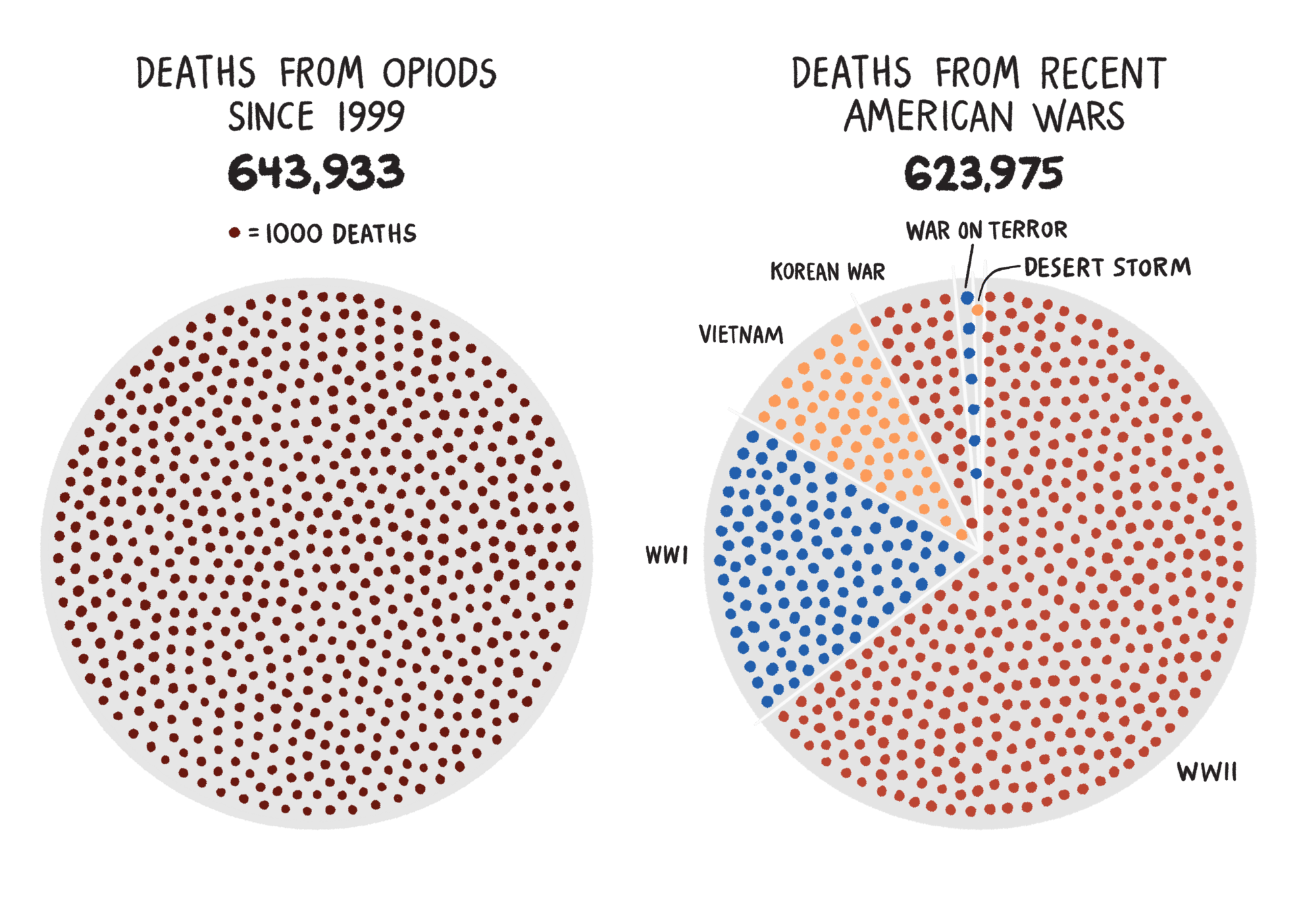

To put it in context, 644,933 people died of an opioid overdose from 1999 – 2021. That's more than all American military casualties from World War I, World War II, the Vietnam War, Korean War, Gulf War and the War on Terror combined.

END 2015

END 2005

END 2010

END 2021

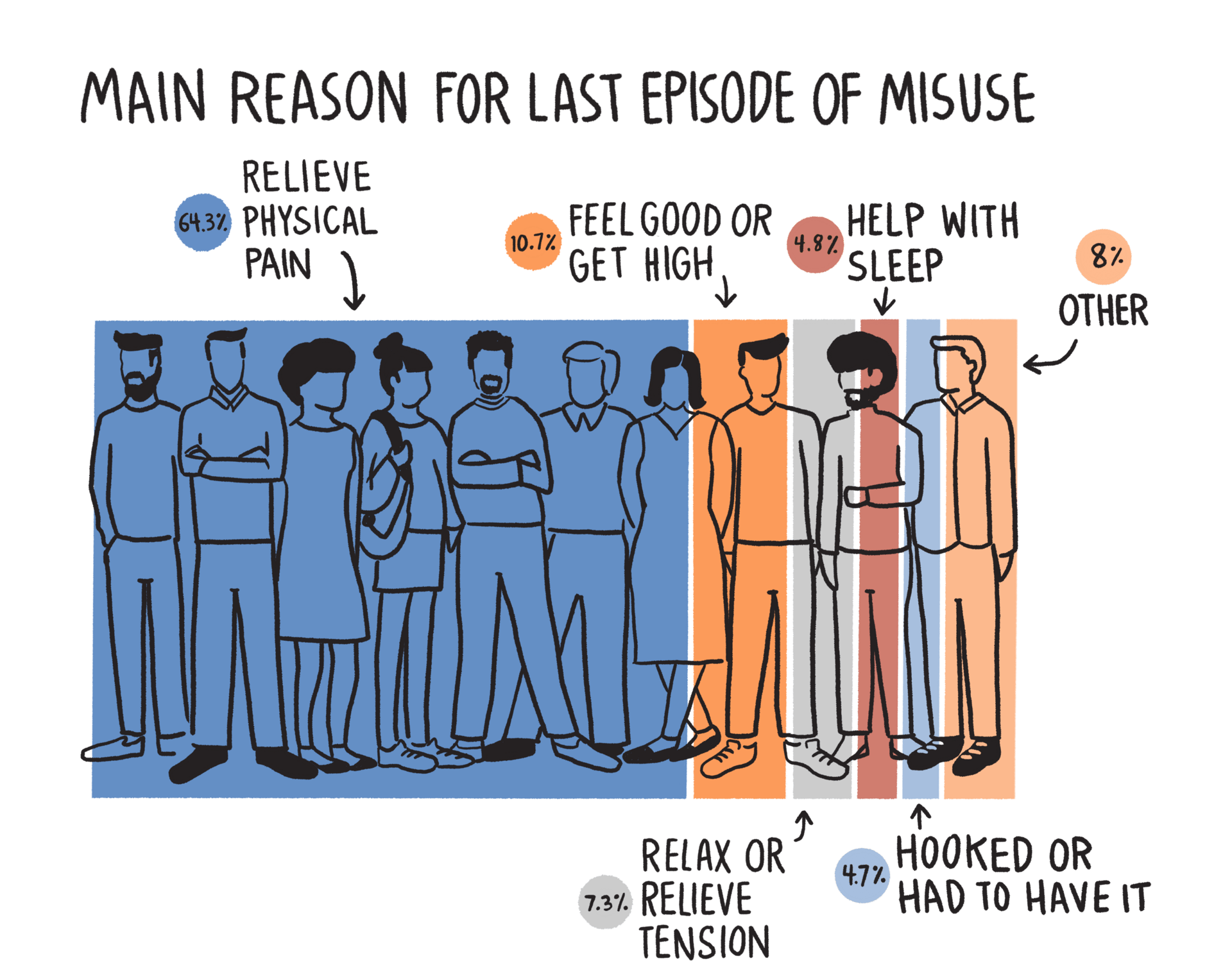

• Taking a prescription in a way or dose other than instructed

• Taking someone else’s prescription

• Taking prescription drugs only to get high

• Mixing prescription opioids with alcohol or other drugs

• Crushing pills or opening capsules, then snorting the powder or dissolving the powder in water then injecting the liquid into a vein.

Some opioids, like heroin, aren’t available by prescription. People use those drugs just to get high.

How do people misuse opioids?

Prescription opioids are prescribed by doctors to treat pain and other health issues, such as following surgery or injury, or for health conditions such as cancer. When used as prescribed and for a short time, opioids are relatively safe. But when they are misused, they can be dangerous.

How do people use opioids?

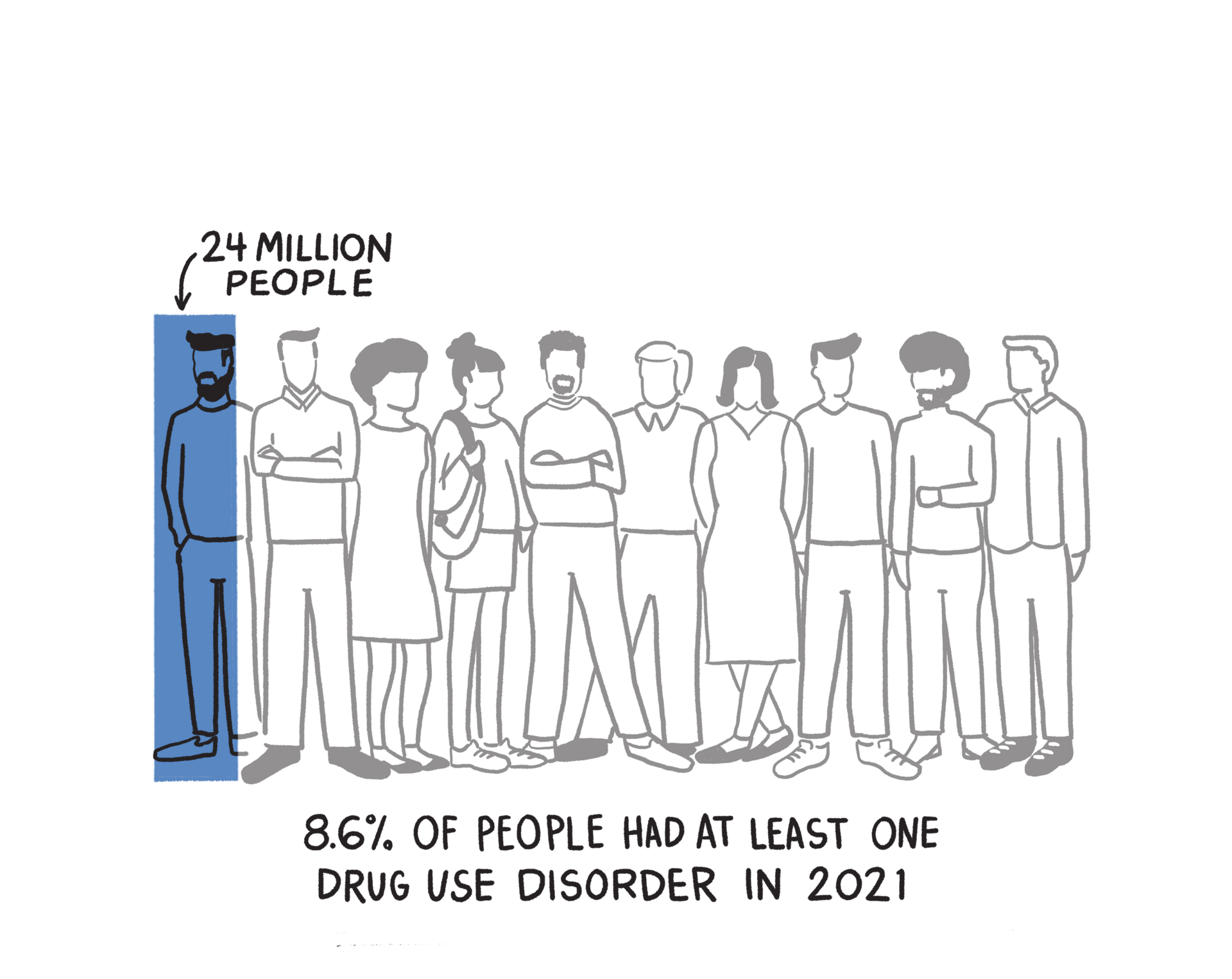

Severe substance use disorders are psychiatric conditions or chronic diseases that often result in relapse. Addictions cause impairments in health, social function, and voluntary control over substance use.

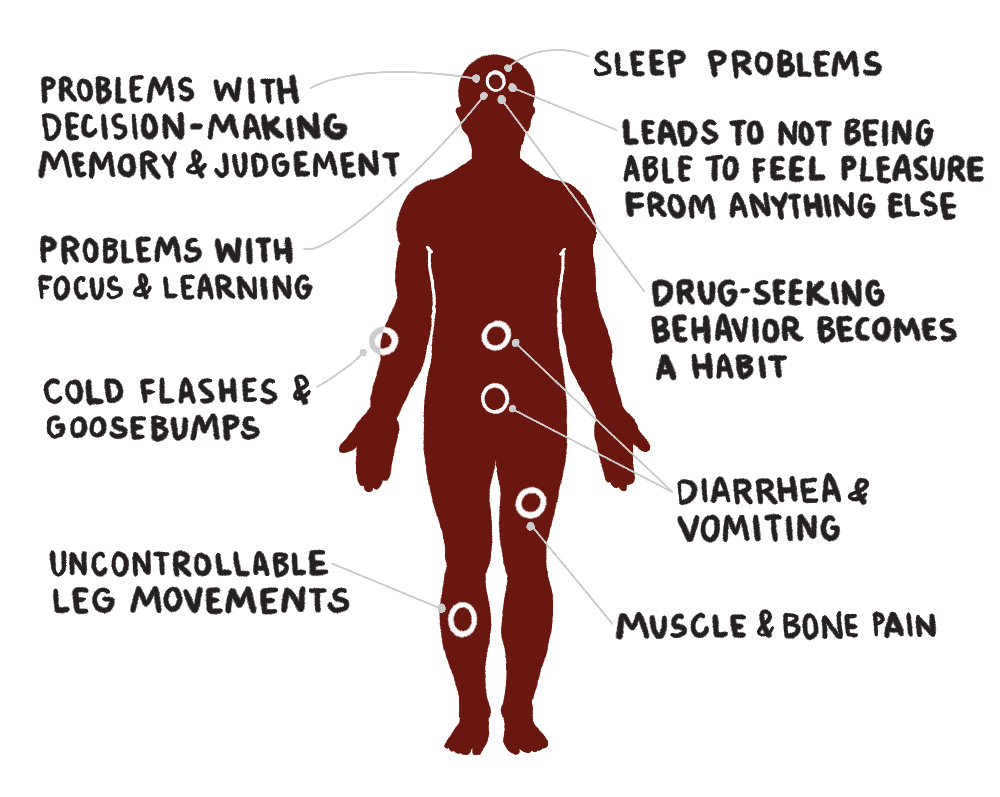

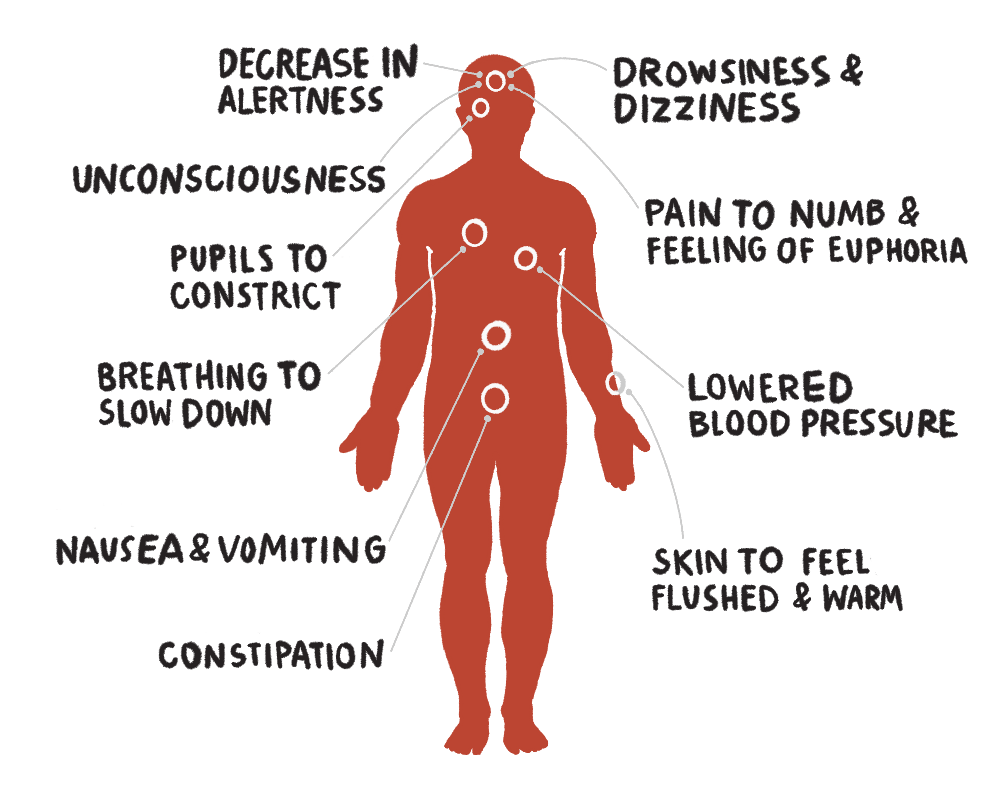

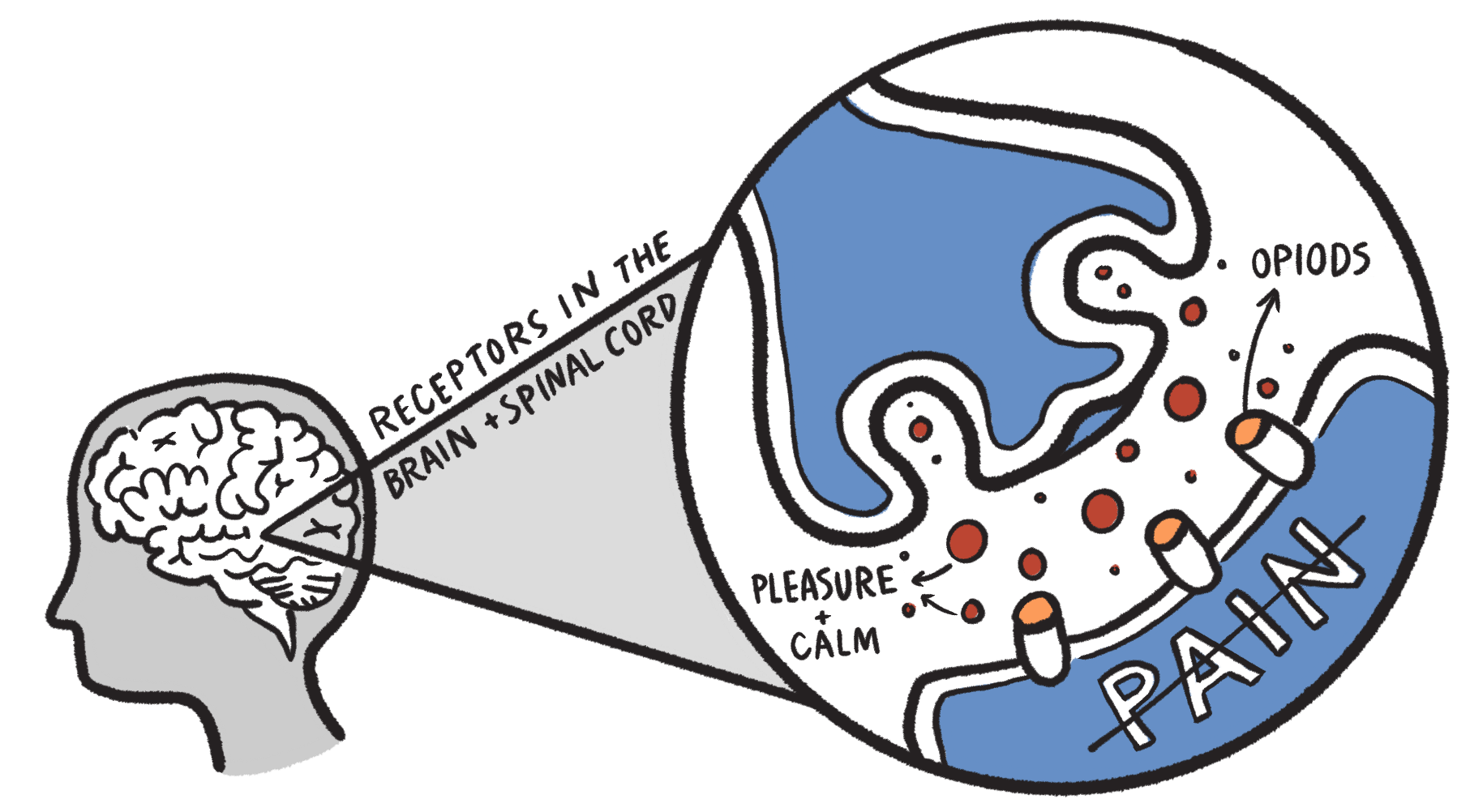

Opioids attach to and activate opioid receptors located in many areas of the brain, spinal cord, and other organs in the body, especially those involved in feelings of pain and pleasure.

When opioids attach to these receptors, they block pain signals sent between the brain and the body and cause dopamine to flood the brain’s reward pathways, inducing feelings of euphoria in the user. The release of dopamine plays a major role in addictive behaviors. It can motivate people to want to take the drug again and again despite risks for serious consequences.

After taking opioids many times, the brain adapts to the drug, tolerating it more and diminishing its sensitivity, making it hard to feel pleasure from anything besides the drug. Tolerance occurs when you need a higher and/or more frequent amount of a drug to get the desired effects. Tolerance is not the same as dependence or addiction.

With continued use, brain regions related to decision-making, memory, and judgement also get physically disrupted. Addiction can also cause problems with focus and learning. Drug seeking behavior becomes a habit rather than a choice or rational decision.

Brain changes from continued exposure endure long after an individual stops using substances and may produce continued, periodic cravings for the substance that can lead to relapse for many years. This helps to explain why addiction is a brain disease, not a matter of willpower.

How do opioids work?

“It’s a psychiatric illness and if we don’t treat it, like any disease, it gets progressively worse.”

Doctor in recovery for SUD*

Even as the addictive nature of OxyContin became increasingly evident, Purdue Pharma, the drug's manufacturer, continued to aggressively market the drug. Despite mounting evidence and numerous court challenges, the company continued to push OxyContin, making billions of dollars as tens then hundreds of thousands of Americans succumbed to opioid overdoses.

In 2016, the CDC issued new guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Those guidelines greatly reduced the flow of OxyContin prescriptions in America. This was a problem for the many Americans who became addicted to a drug they were told was non-addictive.

Anyone consistently using opioid medications is likely to experience tolerance, which may lead to them taking amounts greater than prescribed. As dependence grew, these individuals found themselves trapped in a cycle of addiction, a scenario they never anticipated.

When the CDC's national initiative reduced the numbers of opioids perscribed, many people across America could not get a refill of their prescription opioids and transitioned to something stronger to satiate their cravings.

This surge in demand in 2016 created a huge market for illicit opioids and the supply of heroin couldn't keep pace.

Fentanyl filled the void. It is cheaper and easier to make than heroin and it is a stronger product, so drug dealers needed to make less of it to meet demand.

Fentanyl is highly effective in medical settings because it is fast-acting and doesn't last long. However, for those battling addiction, this short-acting nature is detrimental. Unlike heroin, which can provide relief for a substantial part of the day, the effects of a fentanyl dose are fleeting, lasting only a few hours. This means the user will seek more frequent dosing, heightening the risk of overdose and dependency.

Why would someone take such a dangerous drug? Overdoses can be accidental or intentional. In many cases, fentanyl is mixed with cocaine or methamphetamine without the user's knowledge, and a person with no tolerance to opioids may suffer a fatal overdose.

Illicit Fentanyl Floods the US

Fentanyl is a powerful opioid, first synthesized by Belgian chemist Paul Janssen in 1959. Janssen wanted to develop a pain management drug that was more potent and faster-acting than existing opioids like morphine. Janssen was trying to find a drug that worked better for hospital procedures like open heart surgery.

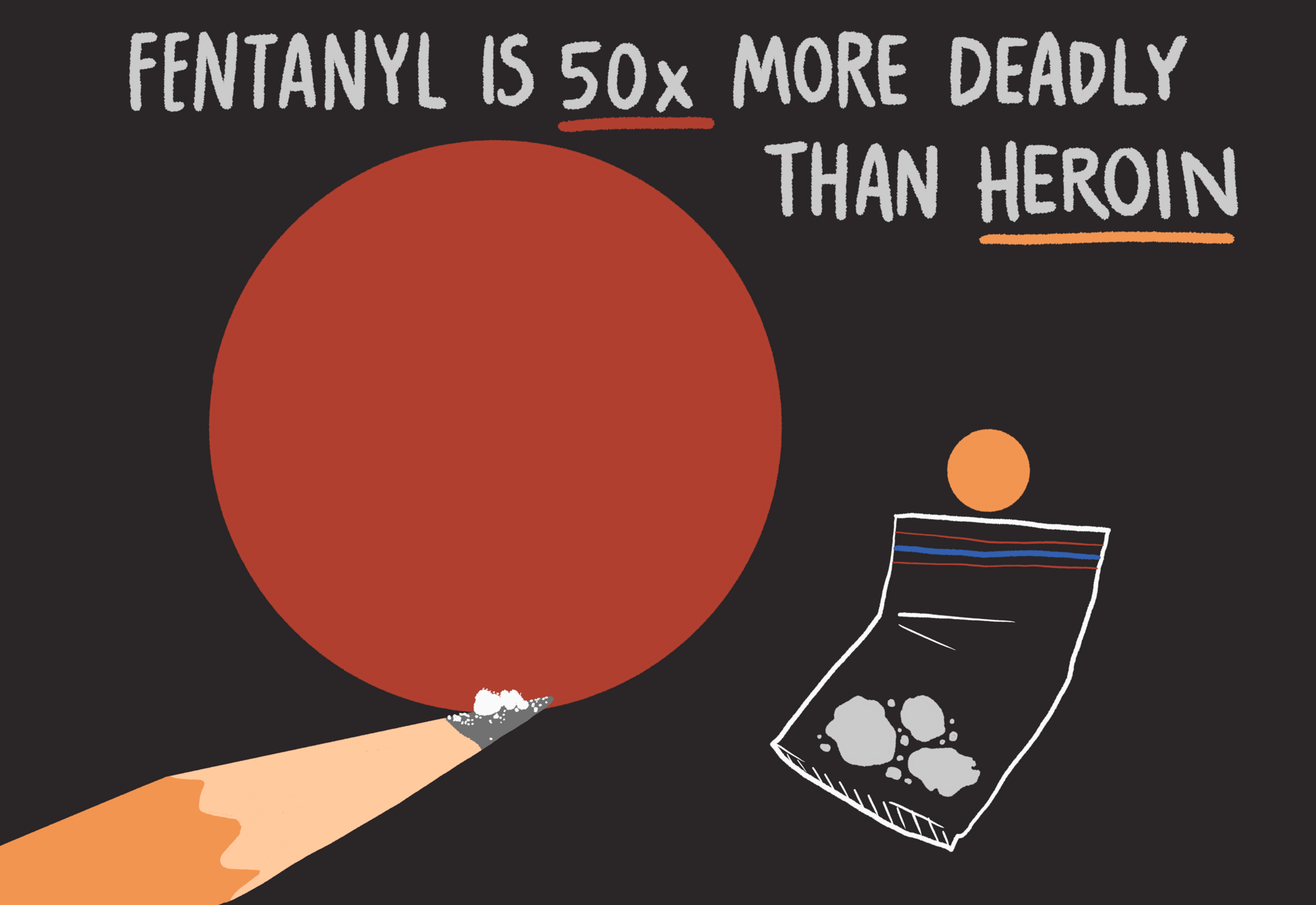

Fentanyl was designed to be strong, allowing for smaller doses to achieve the same level of pain relief as other opioids. Fentanyl is 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin. This potency, combined with its quick action, made it useful in medical settings for managing severe pain, like in surgical procedures or for patients with chronic pain who had developed a tolerance to other opioids.

When prescribed by a doctor, fentanyl can be given as a shot, a patch that is put on a person’s skin, or as lozenges that are sucked like cough drops.

What is Fentanyl?

Steve Chassman, LCSW, CASAC

Executive Director, LICADD

“NYS shut down, you couldn’t go to school, your place of worship... Social isolation, fear, anxiety, and financial insecurity—which all Americans were dealing with during the 2-year COVID crisis—have always been the breeding grounds of self medication.”

COVID exacerbated the opioid epidemic. Although overdose rates were going up before the pandemic, isolation, disruption of addiction services, and other factors related to COVID increased overdose rates further.

COVID brought about unprecedented challenges for dealing with the opioid epidemic. There were disruptions in addiction treatment, recovery services, and the delivery of mental health and harm reduction services. Many people lost their jobs. There was widespread worsening of pre-existing psychiatric conditions. Isolation led to a lack of peer support. These factors may lead to increased opioid use, relapse risk, and overdoses.

During the pandemic, drug use increased in both quantity and frequency, leading to an increase in drug overdose deaths. A likely explanation for the increase in substance use during the pandemic is the challenge of coping with emotional stress, social isolation, economic stress related to COVID-19, and increased general anxiety and depression. The rising number of overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, could be attributed to heroin shortages and the economic downturn during the pandemic, which led to users switching to substances such as low-cost fentanyl.

Impacts of COVID-19

Person in recovery from SUD*

“The only time I wanted to get sober was this small window of time while I was in the hospital and right after. I'm lucky I had people who could help me navigate the healthcare system to get help.”

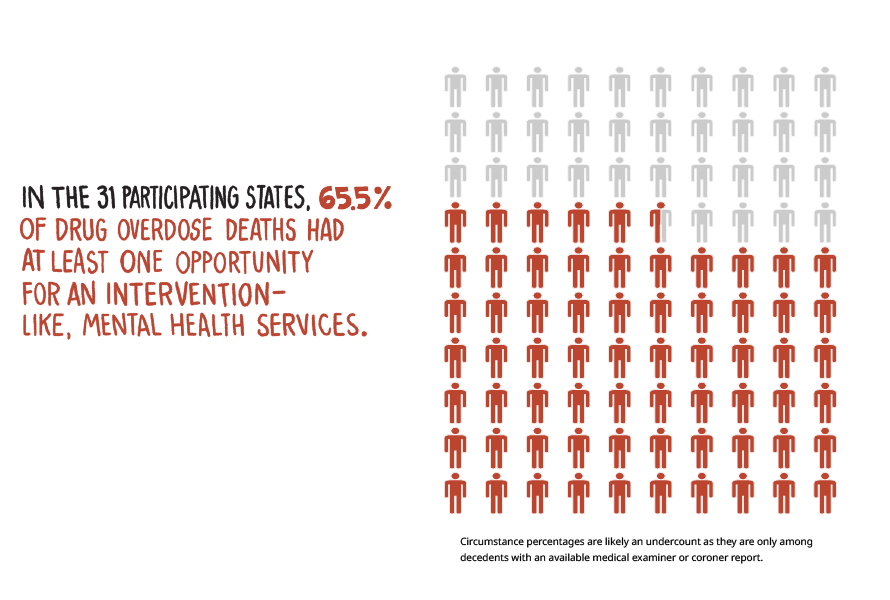

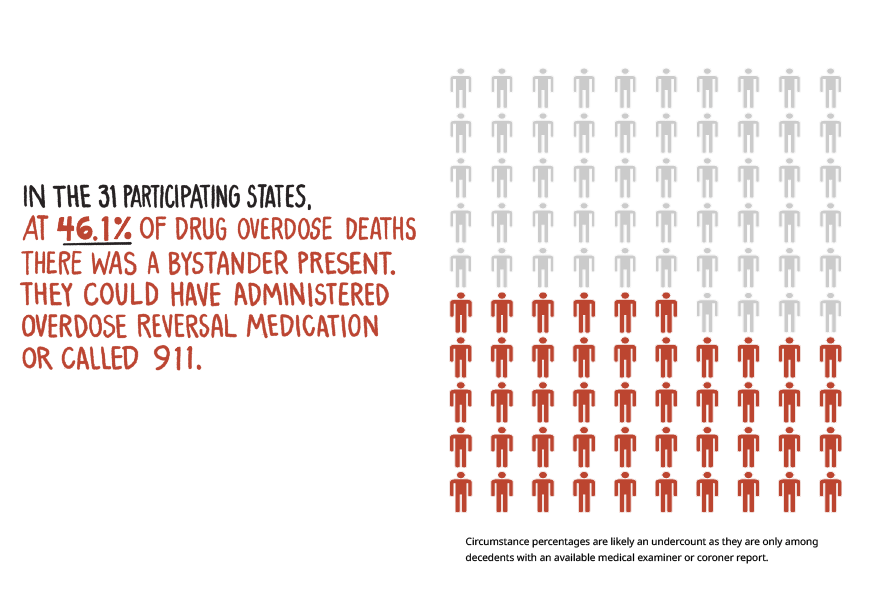

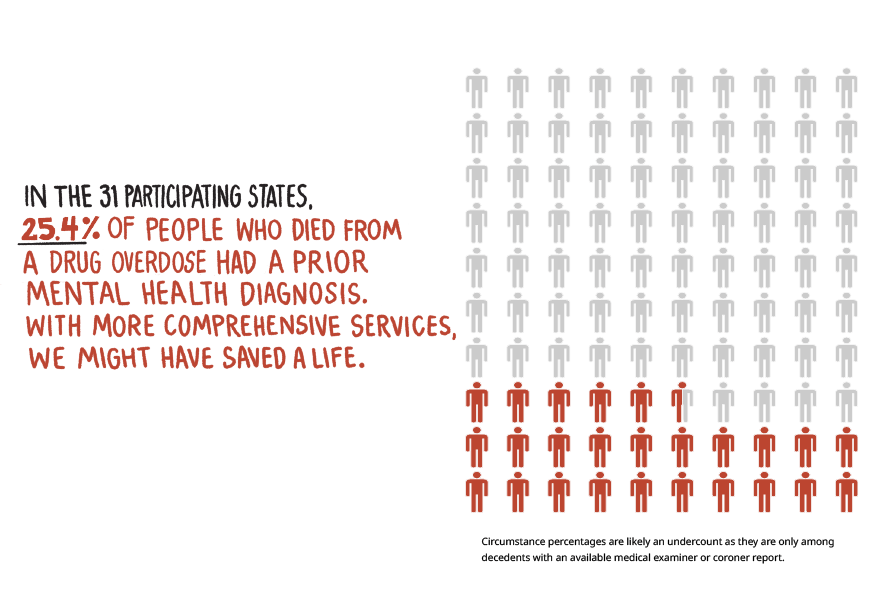

Click through to see the data:

Mental

Health

Diagnosis

Bystander

Present

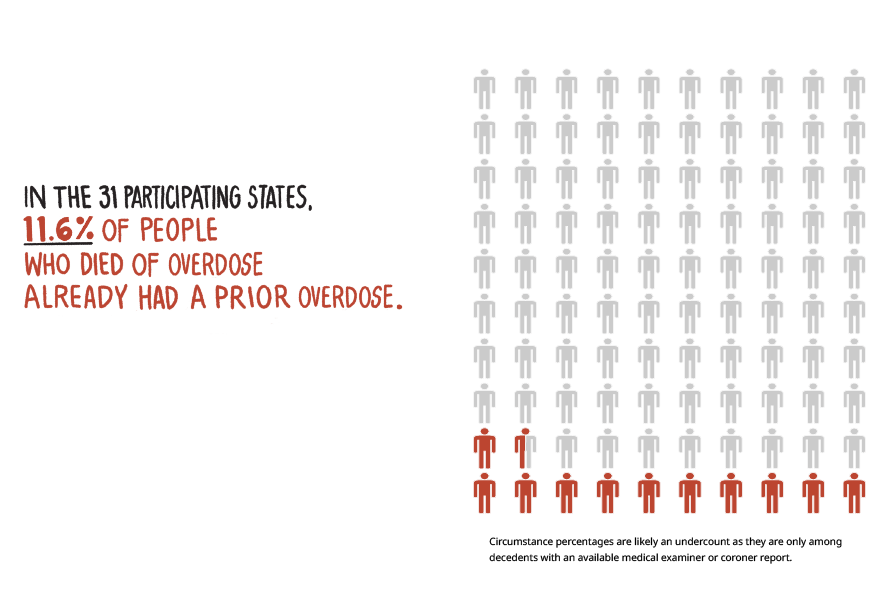

Prior

Overdose

All

Mental

Health

Diagnosis

Bystander

Present

Prior

Overdose

All

All

Mental

Health

Diagnosis

Prior

Overdose

Bystander

Present

Mental

Health

Diagnosis

Prior

Overdose

All

Bystander

Present

Opioid overdoses kill tens of thousands of people every year in the United States. The good news is that scientists have developed a medication called naloxone that can reverse an overdose if given quickly enough. It is carried by most first responders. Families and friends who care for people with opioid use disorder can get an easy-to-use naloxone nasal spray at many pharmacies without a personal prescription to have on hand in case of an emergency.

How can an overdose be treated?

For the user, successful recovery often involves making significant changes to one’s life to create a supportive environment that avoids substance use or misuse cues or triggers. Recovery can involve changing jobs or housing, finding new friends who are supportive of one’s recovery, and engaging in activities that do not involve substance use. This is why ongoing support services in the community after completing treatment can be invaluable for helping individuals resist relapse and rebuild lives that may have been devastated by years of substance misuse.

Parents, friends, and health care professionals can support direct intervention with a person using drugs. We can remain in their lives and encourage the user to take steps towards recovery. Addiction to alcohol or drugs is a chronic but treatable brain disease that requires medical intervention, not moral judgment. It is critical to prevent misuse from starting and to identify those who have already begun to misuse these substances and intervene early.

How can we intervene?

Opportunities for Intervention

(Kansas, Texas and Wyoming do not have a Good Samaritan law for drug overdoses but have a Naloxone Access law.)

"I called 911 for a friend overdosing. Good thing I did.

I wasn't scared to be arrested because I knew most states have a 911 Law for Good Samaritans that protects people who call 911 in that situation This law helped me save a life. We needed help, not punishment."

Person in recovery from SUD*

Drugs Data is an independent anonymous laboratory analysis and drug checking program of Erowid Center. Its purpose is to collect, review, manage, and publish laboratory testing results from our lab and republished from other analysis projects worldwide.

The information is made publicly available to help harm-reduction efforts, medical personnel, and researchers.

DrugsData.org

Drugs can now be checked for fentanyl anywhere someone uses drugs with fentanyl test strips. Drug checking is a harm reduction practice in which people check to see if drugs contain certain substances.

NIDA-funded research shows that some people change their drug use behavior when their drugs test positive for fentanyl. This includes not using alone and using smaller amounts of the drug more slowly.

DanceSafe.org is a drug checking nonprofit that provides programs like drug education, sexual health and consent. DanceSafe is the only nonprofit drug checking kit manufacturer in America.

Drug Checking

At overdose prevention centers, people use illicit substances obtained elsewhere in a controlled setting. Staff are trained to detect and respond to drug overdoses and may connect people to health and support services, including substance use and mental health treatment.

Evidence from more than 20 years of overdose prevention center operations in other countries indicate that no one has died of a drug overdose while at an overdose prevention center. However, it is unclear whether such facilities reduce overdose death rates overall. Studies also suggest that overdose prevention centers are associated with increased access to substance use disorder treatment.

Never Use Alone & Prevention Centers

Anyone can purchase overdose reversal medications, like naloxone. These medications are safe and effective life-saving tools that can be given to someone experiencing a drug overdose.

Narcan can be expensive, but states have been working to make it cheaper and easier to find. Three states — Ohio, Delaware, and Iowa — provide free Narcan. Cities such as Philadelphia and Chicago distribute free Narcan at public libraries.

You can now buy NARCAN Nasal Spray over the counter at CVS Pharmacy without a prescription in all states and in Washington, DC and Puerto Rico.

Overdose Reversal Medications

1-800-662-HELP (4357) is the SAMHSA National Helpline, (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

You can also send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you.

SUD treatment leads to reduced opioid use, and fewer risky behaviors.

Syringe Services Programs (SSPs)

Harm Reduction Resources

Harm reduction is part of a comprehensive prevention strategy and the continuum of care. Harm reduction approaches have proven to prevent death, injury, disease, overdose, and substance misuse. Harm reduction services save lives by being available and accessible in a manner that emphasizes the need for humility and compassion toward people who use drugs.

Harm reduction can range from using in less risky ways (e.g., sniffing instead of injecting) to cutting down on substance use or even seeking abstinence.

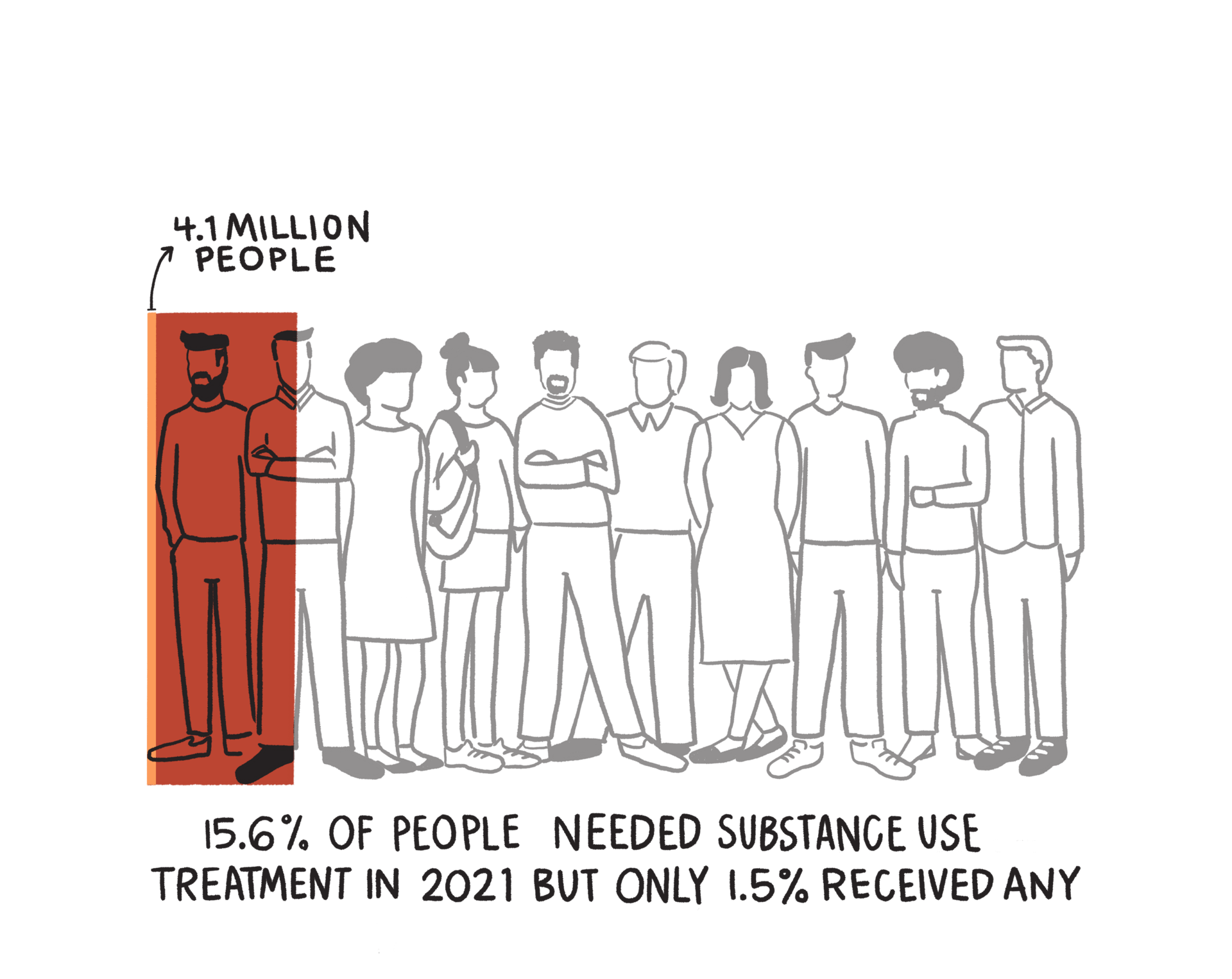

Why don't people receive treatment?

Barriers to treatment entry for treatment programs for participants include: use of stimulants, lack of health insurance, residing far from treatment programs, lack of available appointments, and work or childcare responsibilities. People also self-reported

Harm reduction is an evidence-based, often life-saving approach that directly engages people who use drugs to prevent overdose, disease transmission and other harms.

Harm Reduction Strategies

“Getting people into treatment for substance use disorders is critical, but first, people need to survive to have that choice. Harm reduction services acknowledge this reality by aiming to meet people where they are to improve health, prevent overdoses, save lives and provide treatment options to individuals.

Nora D. Volkow, M.D.

National Institute on Drug Abuse Director

Share your story. Make your voice heard.

Democracy.io allows you to quickly and easily look up who your elected officials are and send them a message of your choosing. You could tell them your story and how you've been impacted by substance use disorder. Or you could write to them about the importance of mental healthcare, substance use disorder treatment, or harm reduction services. Click the button below to send a message to your local representatives.

Write your

elected official

Addiction counselor in recovery from SUD*

"People in deep addiction don’t vote so if you’re trying to raise awareness and make a difference, families and friends need to speak out."

BACK TO TOP

NIDA. 2022, December 16. NIH launches harm reduction research network to prevent overdose fatalities. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2022/12/nih-launches-harm-reduction-research-network-to-prevent-overdose-fatalities on 2023, December 4

US Government Accountability Office. (2021, November 19). Drug misuse: Most states have good samaritan laws and research indicates they may have positive effects. Drug Misuse: Most States Have Good Samaritan Laws and Research Indicates They May Have Positive Effects | U.S. GAO. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-248

Interviews

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023, April 24). Non-prescription (“over-the-counter”) naloxone frequently asked questions. SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/medications-counseling-related-conditions/naloxone/faqs

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (n.d.). SAMHSA’s National Helpline. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 21). Lifesaving Naloxone. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/naloxone/index.html

Never Use Alone Inc. (2023, October 1). Never Use Alone. Retrieved from https://neverusealone.com/

Erowid Center. (2023). DrugsData.org: Lab Analysis / Drug Checking for Recreational Drugs. Retrieved from https://drugsdata.org/

Resources

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22-07-01-005, NSDUH Series H-57). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report

NIDA. 2022, December 16. NIH launches harm reduction research network to prevent overdose fatalities. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2022/12/nih-launches-harm-reduction-research-network-to-prevent-overdose-fatalities on 2023, November 21

NIDA. 2023, October 17. Syringe Services Programs. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/syringe-services-programson 2023, November 24.

NIDA. 2023, August 28. Overdose Prevention Centers. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/overdose-prevention-centers on 2023, November 26.

Surratt HL, Otachi JK, Williams T, Gulley J, Lockard AS, Rains R. Motivation to Change and Treatment Participation Among Syringe Service Program Utilizers in Rural Kentucky. J Rural Health. 2020 Mar;36(2):224-233. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12388. Epub 2019 Aug 15. PMID: 31415716; PMCID: PMC7021582.

Jakubowski A, Fowler S, Fox AD. Three decades of research in substance use disorder treatment for syringe services program participants: a scoping review of the literature. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2023 Jun 10;18(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13722-023-00394-x. PMID: 37301953; PMCID: PMC10256972.

SAMHSA. (2023, April 24). Harm Reduction. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, September 2018.

Harm Reduction

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS). Final Data. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2023, October 15. Access at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22-07-01-005, NSDUH Series H-57). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, September 2018.

Intervention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology (DOSE) System. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; [2023, October, 8]. Access at: https://www.cdc.gov//drugoverdose/nonfatal/dose/surveillance/dashboard/index.html

Chart Four - COVID Causes Spike in ER Visits for Opioid Overdoses

Ahmed S, Sarfraz Z, Sarfraz A. Editorial: A Changing Epidemic and the Rise of Opioid-Stimulant Co-Use. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Jul 6;13:918197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.918197. PMID: 35873238; PMCID: PMC9296817.

Silva MJ, Kelly Z. The escalation of the opioid epidemic due to COVID-19 and resulting lessons about treatment alternatives. Am J Manag Care. (2020) 26:e202–4. 10.37765/ajmc.2020.43386

Parkes T, Carver H, Masterton W, Falzon D, Dumbrell J, Grant S, et al.. “You know, we can change the services to suit the circumstances of what is happening in the world”: a rapid case study of the COVID-19 response across city centre homelessness and health services in Edinburgh, Scotland. Harm Reduct J. (2021) 18:1–18. 10.1186/s12954-021-00508-1

Ahmed S, Sarfraz Z, Sarfraz A. Editorial: A Changing Epidemic and the Rise of Opioid-Stimulant Co-Use. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Jul 6;13:918197. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.918197. PMID: 35873238; PMCID: PMC9296817.

Phillips JK, Ford MA, Bonnie RJ, National National Academies of Sciences and Medicine E . Trends in opioid use, harms, and treatment. In: Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US) (2017).

Enforcement Administration D. 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA). Springfield, VA (2020).

United States Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). One Pill Can Kill. One Pill Can Kill | DEA.gov. https://www.dea.gov/onepill

NIDA. 2021, June 1. Fentanyl DrugFacts. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl on 2023, December 4

Yale Medicine. (2022). How an Addicted Brain Works. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/how-an-addicted-brain-works.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, September 2018.

Mind Matters: Teacher’s Guide. (n.d.). National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIDA_MindMatters_TeachersGuide_2022.pdf

Akpan, N., & Griffin, J. (2017, October 9). How a brain gets hooked on opioids. PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/brain-gets-hooked-opioids

Westhoff, B. (2020). Fentanyl, inc: How rogue chemists created the deadliest wave of the opioid epidemic. Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

NIDA. 2021, June 1. Fentanyl DrugFacts. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl on 2023, November 24

Mind Matters: Teacher’s Guide. (n.d.). National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NIDA_MindMatters_TeachersGuide_2022.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Prescription Opioid Abuse; Phillips JK, Ford MA, Bonnie RJ, editors. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Jul 13. 4, Trends in Opioid Use, Harms, and Treatment. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458661/#

Yale Medicine. (2022). How an Addicted Brain Works. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/how-an-addicted-brain-works.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, September 2018.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1.

Opioids & Fentanyl

Brown University: Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. (2021, July). U.S. & Allied Killed. The Costs of War. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/military/killed

Department of Veterans Affairs. (November 2023). America’s Wars [Fact Sheet]. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2021 on CDC WONDER, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

Keefe, P. R. (2021). Empire of pain: the secret history of the Sackler dynasty. First edition. New York, Doubleday.

Haffajee RL, Mello MM. Drug Companies' Liability for the Opioid Epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 14;377(24):2301-2305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1710756. PMID: 29236640; PMCID: PMC7479783.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2020, November 24). Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Fraud and Kickback Conspiracies. Retrieved November 24, 2023, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/opioid-manufacturer-purdue-pharma-pleads-guilty-fraud-and-kickback-conspiracies. Press Release #: 20-1282

Vogt, PJ (Executive Producer). (January 2023 - present). Search Engine: Why are drug dealers putting fentanyl in everything? [Audio podcast]. Audacy, Jigsaw. https://pjvogt.substack.com/p/welcome-to-search-engine

Vogt, PJ (Executive Producer). (January 2023 - present). Search Engine: Why are drug dealers putting fentanyl in everything? (Part 2). [Audio podcast]. Audacy, Jigsaw. https://pjvogt.substack.com/p/welcome-to-search-engine

Big Pharma

National Safety Council . (2023, March 13). Drug Overdoses. Injury Facts: Safety Topics - Drug Overdoses. https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/home-and-community/safety-topics/drugoverdoses/data-details/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2021 on CDC WONDER, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, July 6). Vital Signs: Opioid Prescribing. Retrieved from https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/vitalsigns/opioids/infographic.html

Chart One - Candlelight Vigils: Opioid Overdose Deaths (1999 - 2021)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, October 2). Opioids. National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/opioids

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS). Final Data. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2023, October 15. Access at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/fatal/dashboard

Opioids Definitions